Mike Wellsbury-Nye – Architectural Technologist

26.10.2023

If you’ve never been to the Design Museum in Kensington, London, we highly recommend that you make the trip. Not only does the museum host exhibitions covering all aspects of contemporary design, from Surrealism to skateboarding, there’s also the Designer Maker User permanent display, highlighting design classics throughout the years, including a favourite of ours here at Place: the iconic iMac G3.

As well as the fantastic displays and exhibits, the collection is housed in a landmark Grade II* listed building in the heart of Kensington’s cultural quarter. Designed by RMJM and extensively modified by John Pawson, the building features a sweeping copper-clad roof, and is considered one of the most important examples of post-war architecture in the country.

When PLACE Architects attended, the museum was hosting a fascinating, and extremely pertinent exhibition on how to build a low-carbon home. The displays focused primarily on the use of straw, stone and wood – three ancient building materials that designers are finding new possibilities for in a future low-carbon construction industry.

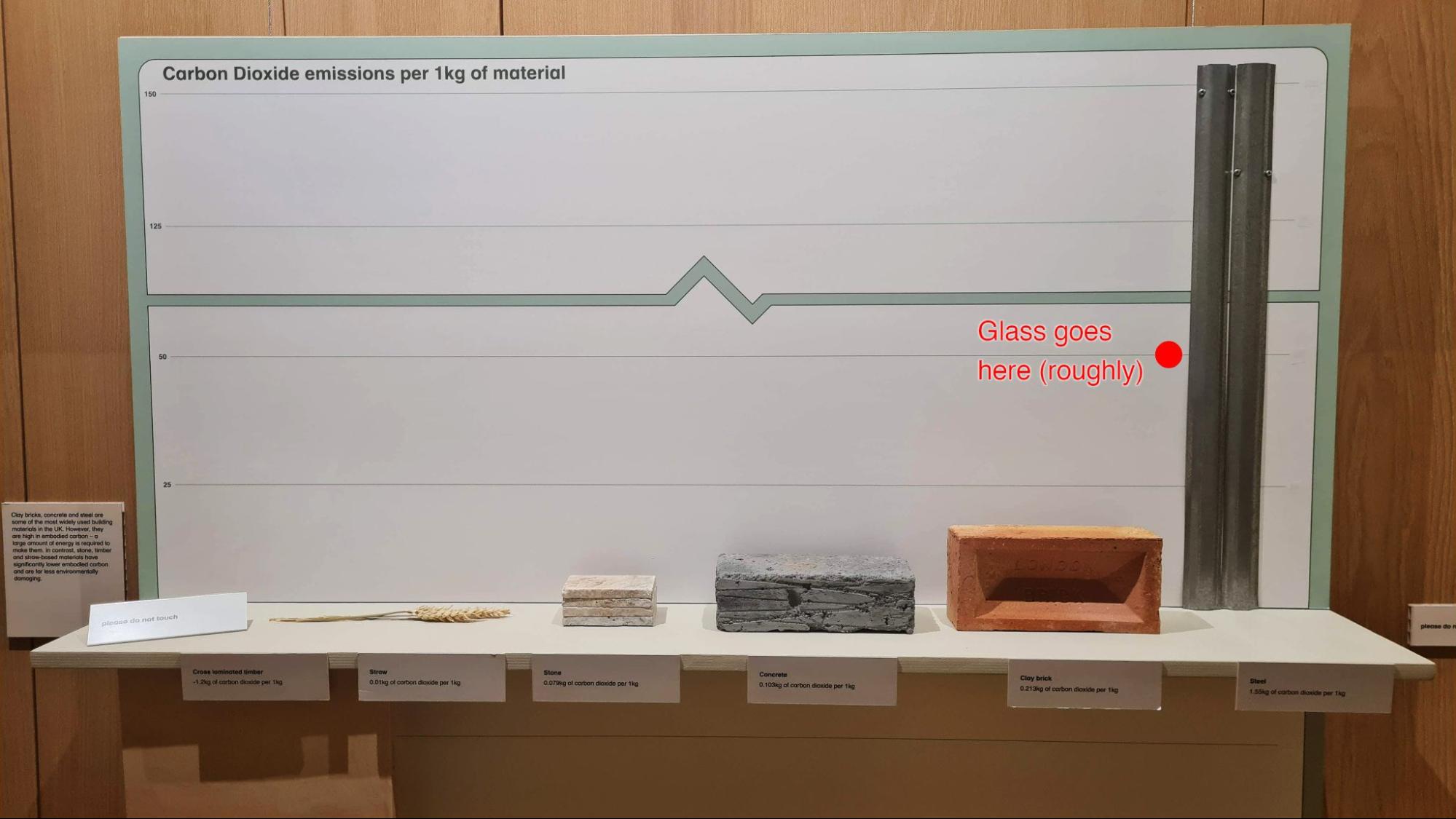

Part of the exhibition highlighted the low embodied carbon of these materials when compared with other, more commonly used materials, such as concrete, brick and steel. And while it’s certainly true that designers will need to consider the inclusion of these higher-carbon materials much more carefully in the future, as we build towards regulation of a construction project’s embodied carbon, one high-carbon material was conspicuous by its absence: glass.

Glass production is a highly energy intensive process, and while recycling clearly helps reduce the embodied carbon, the amount of glass that is recycled varies significantly from region to region. Glass recycling schemes in the UK currently lag behind our neighbours in the EU.

To compound the issue, Insulating Glass Units (IGUs) have a typical lifespan of around 30 years, which is often significantly less time than the rest of the facade materials. These flat glass used for these units cannot contain any imperfections or colour variations, meaning that only material recycled from other glazing is suitable for use. Unfortunately, most glazing is not recycled to make new IGUs.

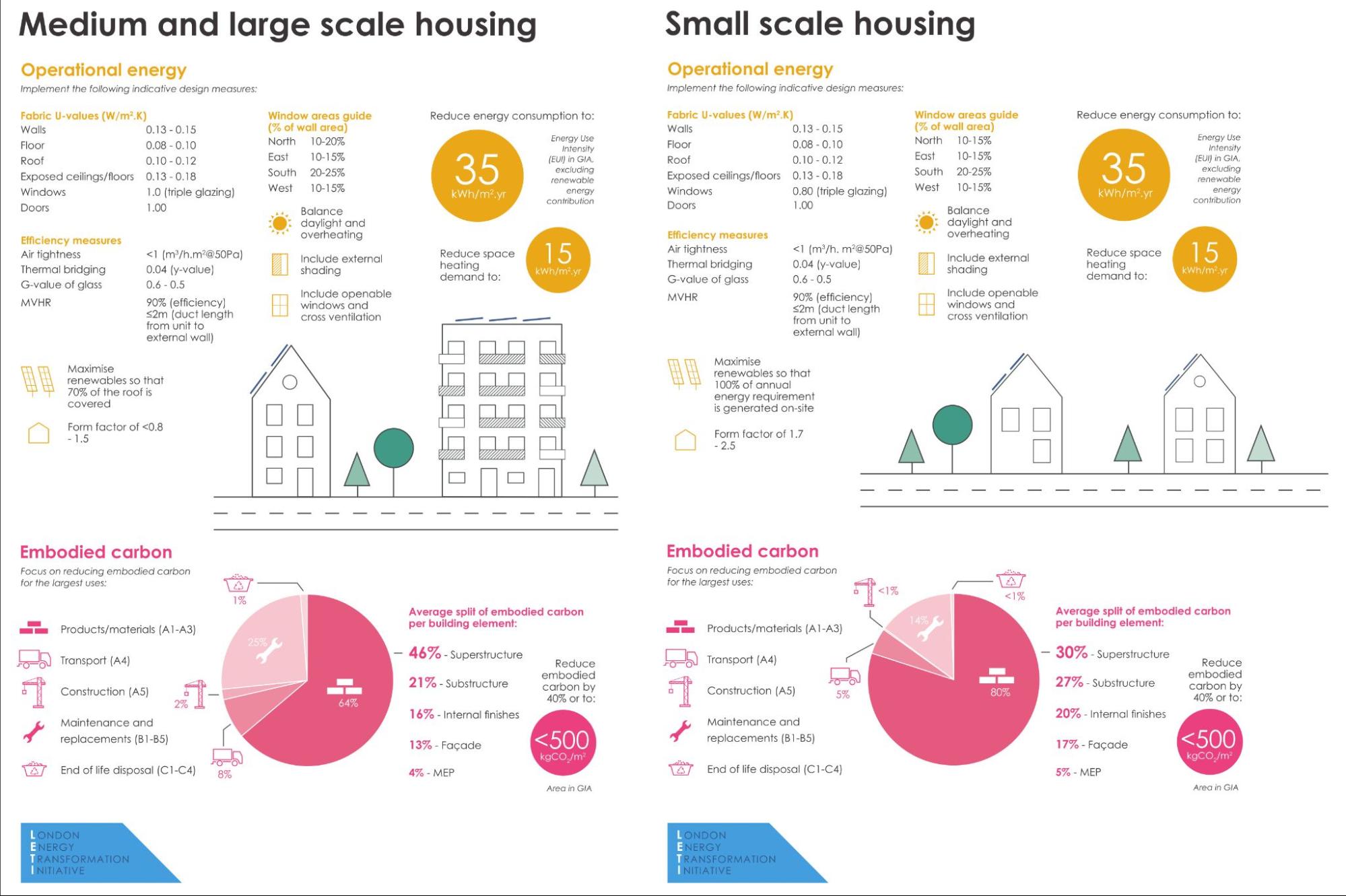

A building’s facade – the external envelope of masonry, cladding, glazing etc – can contribute up to 31% of a building’s embodied carbon, with glass contributing from around a quarter to nearly two thirds of this total, depending on the facade type. On top of all these figures is the fact that a building’s fenestration is often the least thermally efficient part of a building’s envelope, and contributes to operational carbon output through both thermal losses and, if poorly placed, overheating from unwanted solar gain.

And yet, from soaring towers like the Shard, to bespoke houses with panoramic floor-to-ceiling glazing, to more modest highly-glazed domestic extensions, our love affair with glass continues unabated. LETI’s Climate Emergency Design Guide suggests guideline percentages of 10-25% of wall area for domestic new domestic properties, and reducing the contribution of the building’s facade to 13-17%, as well as driving down overall embodied carbon in construction. It is clear that we, as architects and clients, have some challenges ahead of us.

This blog was not written to demonise the use of glass. Glazing can open up a building’s interior to natural light, ventilation, and beautiful views. Natural light has many health benefits, including improving our mood, and helping our circadian rhythm. Good window design and placement can help with solar gain in the colder months, and natural light obviously reduces the need for artificial lighting. Plus, any connection to the outside world can benefit our mental health – although views from semi-exposed external spaces, such as a sheltered balcony, are no less stunning (though they can be a rather more brisk experience on a cold Cornish morning!)

As with all other construction materials, we need to carefully consider the placement, scale, and specification of glazed elements in order to minimise the material’s environmental impact while maximising its undoubted strengths. PLACE Architects’ commitment to designing beautiful, thoughtful, sustainable buildings ensures that we are perfectly placed to help guide you through your project and navigate these considerations, from design, to construction, to completion.

Written by Mike Wellsbury-Nye

As PLACE’s Architectural Technologist and hipster-in-residence, Mike enjoys craft beer, kombucha, waxed moustaches, Nike Air Dunks, and everything from hardcore punk and Hip Hop, to folk session singalongs. He can often be found in his shed, brewing his own German IPA recipes, or trying to perfect his Delirium Tremens clone.